The preparation of red meat can involve numerous cooking methods, often classified as either dry-heat cooking methods (e.g. fried, oven baked, oven grilled, roasted, outdoor grilled / braai) or moist-heat cooking methods which involve the preparation of meat in liquid (e.g. boil, stew, casserole or potjiekos in the South African context).

Factors affecting choice of cooking methods

- The quality and tenderness of the raw meat cut.

- The fat content of the raw meat cut and the desired fat content of the cooked meat.

- The health consciousness of the consumers.

- The desired quality attributes that should be present in the final dish.

- The available food preparation facilities and equipment.

- The eating occasion (e.g. preparing an everyday meal or entertaining guests).

- The time available to prepare the meal.

In 2016/2017 the South African red meat industry funded a comprehensive consumer study to investigate the red meat behaviour and perceptions of the South African low-, middle- and high-income consumers in the Western Cape (n=750). The study sample was designed to reflect the income, ethnic and age groups of the South African population in the Western Cape.

The focus of this article is to explore the red meat cooking behaviour of consumers across the socio-economic spectrum in the Western Cape province of South Africa.

Table 1: Cooking methods applied during the week and over week-ends. (Source: Survey results.)

| Week-day meals | Week-end meals | |||||

| Share of sample applying particular cooking method*: | ||||||

| Marginalised (n=250) | Middle-income (n=250) | Affluent (n=250) | Marginalised (n=250) | Middle-income (n=250) | Affluent (n=250) | |

| Fry | 98% | 78% | 81% | 96% | 81% | 85% |

| Stew | 96% | 87% | 84% | 98% | 65% | 58% |

| Bake/roast | 36% | 65% | 65% | 66% | 76% | 84% |

| Boil | 85% | 64% | 57% | 74% | 48% | 50% |

| Braai | 16% | 31% | 41% | 69% | 80% | 82% |

| Casserole | 28% | 26% | 50% | 25% | 20% | 42% |

| Microwave | 5% | 30% | 30% | 4% | 26% | 23% |

| Top 3 options | Fry Stew Boil | Stew Fry Bake/roast & boil | Stew Fry Bake/roast | Stew Fry Boil | Fry & Braai Bake/roast Stew | Fry & Bake/roast Braai Stew |

* Dominant cooking methods indicated in bold.

Week vs. weekend cooking

A significantly larger share of marginalised consumers applied stewing, frying and boiling during the week and over weekends, while a significantly lower share of these consumers applied baking/roasting, casserole, braai and microwave cooking.

The dominant cooking methods among marginalised consumers in the Western Cape are stewing and frying (applied by more than 95% of the sample during the week and over weekends), followed by boiling. Over weekends these consumers also indicated a preference for braai and oven baking or oven roasting (about two thirds of the marginalised sample).

During the week middle-income households prefer stewing (applied by 87% of the middle-income sample) and frying (78%), followed by bake/roast and boiling (65% each). Over weekends this group focused mainly on frying and braai (80%), followed by oven baking (76%) and stewing (65%).

More than 80% of affluent consumers in the Western Cape preferred stewing and frying during the week, followed by baking/roasting (65%) and boiling (57%). During the week-end the preference of these consumers leaned towards frying, baking/roasting and braai (more than 80%), followed by stewing (58%).

Time to prepare red meat for a main meal

The meat preparation time for the majority of marginalised consumers was 31 to 60 minutes during the week and over weekends. Middle-income consumers typically spent up to 30 minutes on meat cooking during the week and over weekends. The affluent group revealed more varied results, with an equal split between the share of the affluent sample using less than 30 minutes and between 30 and 60 minutes to prepare meat during the week.

The longer cooking times of less affluent consumers could potentially be attributed to the purchasing and preparation of cheaper, less tender cuts with longer cooking times. Over weekends longer cooking times typically applied, and even more so when entertaining guests. This result could likely be due to more complex recipes chosen to prepare food over weekends and when entertaining.

Perceptions regarding long cooking times

For beef, 55% of the total sample perceived red meat as having a long cooking time. Middle-income consumers and marginalised consumers were the most negative in this regard (with 65% and 59% perceiving that beef have long cooking times), while only 41% of the affluent sample reported that beef had long cooking times. For mutton/lamb, approximately a quarter of the total sample perceived the meat type as having a long cooking time.

Perceptions regarding versatility

- On average beef were perceived as being more versatile than mutton/lamb.

- With regard to beef, 83% to 96% of the various income groups perceived beef as versatile.

- For mutton/lamb, 56% to 94% of the various income groups perceived mutton/lamb as versatile.

- Middle-income and affluent consumers were the most positive about the versatility of beef and mutton/lamb.

- Marginalised consumers were relatively more positive about the versatility of beef than mutton/lamb.

Figure 1: Versatility of red meat types.

Perceptions regarding ease of cooking

- On average mutton/lamb was perceived as being easier to cook than beef.

- Mutton/lamb was perceived as being easy to cook by 77% to 94% of the various groups.

- Beef was perceived as being easy to cook by 73% to 81% of the various groups.

- Middle-income and affluent consumers were the most positive about cooking ease of beef and mutton/lamb.

Figure 2: Perceptions regarding ease of cooking red meat.

Confidence when preparing red meat

- On average consumers were slightly more positive about their beef preparation knowledge than for mutton/lamb.

- For beef, 86% to 95% of the various groups perceived that they know how to prepare the meat type.

- For mutton/lamb, 77% to 98% of the various groups perceived that they know how to prepare the meat type.

- Middle-income and affluent consumers were the most positive about their red meat preparation knowledge.

Figure 3: Confidence in respect of meat preparation knowledge.

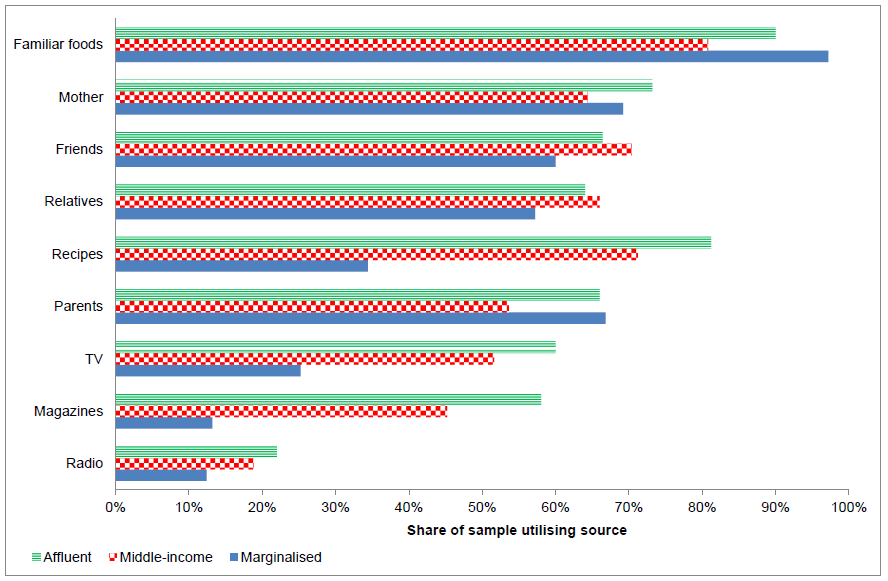

Getting ideas for meal preparation

- Across the socio-economic spectrum the preparation of familiar foods and ‘social sources’ (e.g. mother, parents, friends, relatives) were important.

- Recipes were important to middle-income and affluent consumers (utilised by 71% and 81% of the respective samples).

- Television and magazines were used by approximately 60% of affluent consumers and 50% of middle-income consumers.

Figure 4: Sources used for meal preparation ideas.

Food for thought

The time duration allocated to the preparation of meat within the main meal, was generally shorter during the week than over weekends. Product development, recipe development and consumer education should thus be focused on (1) quick and tasty meal ideas based on red meat for weekdays, and (2) more time consuming red meat-based meal ideas for weekends and when entertaining guests.

Research is needed on how the cooking times of less expensive and less tender red meat cuts could be decreased.

The results indicate that red meat is generally viewed as a very versatile food option, creating an opportunity for our red meat industry to show consumers even more ways to enjoy beef and mutton/lamb. However, with affordability being the major red meat constraint cited by consumers, a major challenge is to also provide consumers with red meat-based meal ideas that expand the versatility of red meat dishes based on perhaps less expensive red meat cuts.

When preparing meals, most consumers rely on the preparation of familiar foods and ideas obtained from ‘social sources’ such as family and friends. Recipes, television and magazines were the best ‘external’ sources of meal preparation ideas.

Considering the severe increase in overweight and obesity in South Africa, additional consumer education is needed to help consumers learn how to prepare lean red meat in tasty ways, without the addition of fat. From a health perspective, consumers should be motivated to move away from frying as a popular cooking method, given the significant use of additional cooking fat involved in frying. Social media could potentially be a valuable tool in this regard. Literature references available on request by emailing hester@bfap.co.za. – Hester Vermeulen, Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy & Department of Animal and Wildlife Sciences, Dr Beulah Pretorius, Department of Animal and Wildlife Sciences, and Prof Hettie Schönfeldt, Department of Animal and Wildlife Sciences & SARChI Chair, University of Pretori

Acknowledgements: The authors acknowledge(s) funding from RMRD SA, as well as from the Department of Science and Technology (DST), National Research Foundation (NRF), South African Research Chairs Initiative (SARChl) in the National Development Plan Priority Area of Nutrition and Food Security (Unique number: SARCI170808259212). The grant holders acknowledge that opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in any publication generated by the NRF-supported research, are that of the author(s), and that the NRF accepts no liability whatsoever in this regard.