Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

The last official block test performed on South African beef and sheep carcasses was done in 1995. The objective of these block tests was the pricing of red meat cuts. The average weight of carcasses, especially those of cattle, have increased significantly since then (from an average of 240kg to the current average of around 280kg). The percentage that each cut contributes to the carcass as a whole could therefore have changed because of these heavier weights; it could also have altered the factors for calculating the retail price of the different cuts.

Two researchers at the University of the Free State (UFS), Prof Arno Hugo of the Department of Animal Science, and Dr Frikkie Maré, formerly of the UFS Department of Agricultural Economics and currently CEO of the Red Meat Producers’ Organisation (RPO), conducted a preliminary block test on one side of an A2 beef carcass and an A2 lamb carcass. This was done at the request of Red Meat Research and Development South Africa (RMRD SA), the aim being to reveal to what extent the situation has changed.

Method of investigation

The carcasses were purchased from a butcher in Bloemfontein and taken to the meat science laboratory at the university. Prof Hugo processed the carcasses into cuts as per standard retail methods. Because only one beef hindquarter was available, it was cut in three different ways and reassembled for calculation purposes:

- T-bones and club steaks were prepared, and the rump fillet removed.

- The entire fillet was removed, and the whole rump prepared as club steaks.

- The entire loin (striploin) and fillet were removed.

The lamb carcass was cut in two different ways: one side conventionally, and the round shoulder removed from the opposite side before processing it into cuts.

Dr Maré handled the financial aspects of the test and calculated the block test’s factors for the beef and lamb carcasses. Tables 1 and 2 contain the final block tests and calculations.

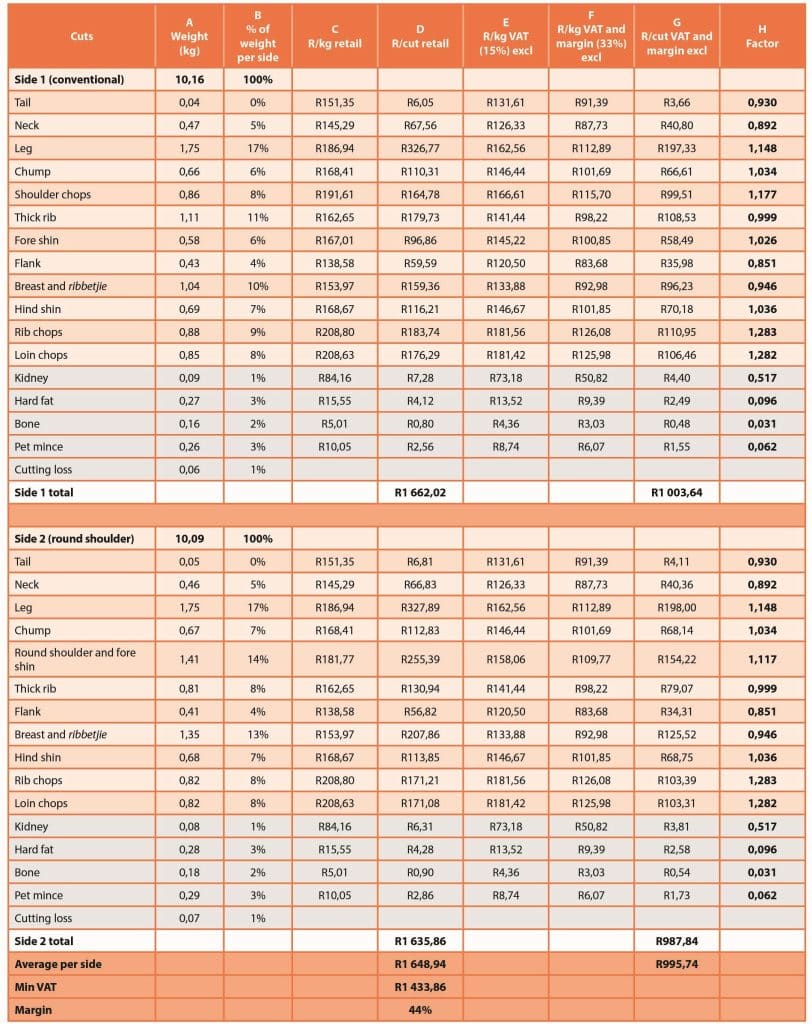

Lamb block test (Table 1)

- The A2 lamb carcass weighed 20,25kg. The abattoir price for the carcass at the time was R98,31/kg.

- The carcass was divided into two sides, and each was cut differently: side 1 = conventional, and side 2 = round shoulder.

- Columns A and B reflect the carcass data as determined in the block test. Column A represents the total weight of each cut, and B the percentage of the side’s weight.

- Column C contains the average R/kg retail price (average price of six retailers) of the cut, while column D represents the shelf price of the cut (R/kg x weight).

- Column E is the shelf price minus VAT (15%), and column F is the price minus VAT and margin (44%).

- The 44% margin is the difference between the farmgate carcass price per side (R995,39) and the average total the side sells for in the retail market, excluding VAT (R1 433,86).

- Row G represents the total value of each cut, excluding VAT and margin, and is included in the table as a test to see whether the total average value of the two sides (R995,74) equals the average carcass price (R995,39) of the sides.

- The factor in column H was calculated by dividing the value of each side in column F (R/kg, excluding VAT and margin) by the R/kg carcass price (R98,31).

- The factor denotes the price of each cut and represents the demand and supply of the cut. Popular cuts in high demand will have a higher factor, and low-demand cuts a lower factor. A factor of one represents the carcass price, meaning that a cut with a factor of more than one sells for more than the carcass price (before VAT and margin). Cuts with a factor of less than one sell for less than the carcass price. The most expensive cuts on a lamb carcass are therefore the rib and loin chops. Use the following formula to calculate the shelf price of rib chops: shelf price (R208,80/kg) = carcass price (R98,31/kg) x factor (1,283) x margin (1,44) x VAT (1,15).

Table 1: Block test for lamb.

The same procedure was followed for the beef block test (Table 2), the only difference being that the side was divided into two quarters.

- The A2 beef carcass side weighed 149,6kg. The abattoir price for a carcass at the time was R61,50/kg.

- The side was divided into a forequarter (71,4kg) and hindquarter (79,82kg). There were alternatives for cutting the hindquarters (alternatives 1 to 3).

- Columns A and B reflect the carcass data as determined in the block test. Column A represents the total weight of each cut, and B the percentage of the quarter’s weight.

- Column C contains the average R/kg retail price (average price of six retailers) of the cut, while column D represents the shelf price of the cut (R/kg x weight).

- Column E is the shelf price minus VAT (15%), and column F is the price minus VAT and margin (33%).

- The 33% margin is the difference between the farmgate carcass price for the side (R9 300,03) and the average total the side sells for in the retail market, excluding VAT (R12 411,95).

- Row G represents the total value of each cut, excluding VAT and margin, and is included in the table as a test to see whether the total average value of the side (R9 333,41) equals the carcass value of the sides (R9 300,03).

- The factor in column H was calculated by dividing the value of each side in column F (R/kg, excluding VAT and margin) by the R/kg carcass price (R61,50).

- The factor denotes the price of each cut and represents the supply and demand of the cut. Popular cuts will have a higher factor, and less popular cuts a lower factor. A factor of one represents the carcass price, meaning that a cut with a factor of more than one sells for more than the carcass price (before VAT and margin), and a factor of less than one sells for less than the carcass price. The most expensive cut is the fillet. Use the following formula to calculate the shelf price of fillet: fillet shelf price (R223,90/kg) = carcass price (R61,50/kg) x factor (2,380) x margin (1,33) x VAT (1,15).

Table 2: Block test for beef.

Conclusions

In terms of the block test for lamb, the researchers concluded that the factors of all cuts, excluding the low-value cuts highlighted in grey in the table, are very close to each other, the highest being 1,283 (rib chops) and the lowest 0,851 (loin). This shows that there is very little price differentiation between the different lamb cuts. Moreover, all the factors are relatively close to one (1). While the margin of 44% may seem high, it is important to note that is the margin for the entire value chain and not just the retail margin. Compared to the standard retail margin of 30%, the 44% margin for the value chain as a whole is well within limits.

An aspect to note is that the standard deviation between the retail prices of some cuts constitutes as much as 25% (rump) of the average price, the lowest being as little as 8% (rib chops and shoulder). The prices of cheaper cuts vary much more than the prices of more expensive cuts.

The industry can benefit

from a standardised block

test performed by an

independent institution.

As for the beef block test, the researchers noted that the factors of the cuts, excluding the low-value cuts highlighted in grey in the table, exhibit a bigger variance than in the case of lamb, ranging from a high of 2,380 (fillet) to a low of 0,973 (short rib). This indicates that beef cuts are more clearly differentiated than lamb cuts. In the case of lamb, the factors are not only close to each other but also close to one (1). As for beef, there is a greater difference between factors.

The average value chain margin of 33% is very close to the retail margin before VAT of 30%. The retailer therefore has a smaller margin on beef than on other products. The standard deviation between retail prices as a percentage of the average retail price was slightly lower for beef, 22% (rump tail) being the highest and 7% (thin flank) being the lowest.

Comparing the factor results of this test to 1995’s factors, the factors of the different lamb cuts seem to have remained the same for the most part. For beef, the factors appear to have increased, but only for some cuts. The factors of a few of the more popular cuts, such as rump and loin, are lower than in the past.

The researchers emphasised that, although this was a small, preliminary project, it clearly shows that the cut factors, especially for beef, have changed over time. Whereas this can be attributed to the heavier carcass weights, other factors such as changing consumer preferences, may also contribute.

This initiative, they emphasise, can serve as a precursor to a larger project that includes aspects such as different carcass weights, fat classification, age groups, and breeds.

Food security

Although South Africa generally produces enough food, it is not always affordable, leading households to often be left food insecure, says Dr Maré. Too many households simply cannot afford to buy enough food.

“A characteristic of red meat, compared to chicken for example, is that each carcass has cuts that sell for lower prices than the average carcass price. Red meat therefore has a key role to play in terms of food security at household level. Here I am not only referring to the cheaper carcass cuts but also the fifth quarter.”

For example, he points out, the price of liver in South Africa is somewhat higher than in Western countries, precisely because it is in high demand as a relatively cheap red meat option. As a result, liver is imported from countries in which it is deemed a low-value product.

High- and low-value cuts differ in terms of the cooking methods used. High-value cuts are associated with dry cooking methods such as braising and baking, whereas low-value cuts are associated with wet cooking methods such as prolonged steaming and boiling to get the meat tender.

“When it comes to price, the high-value cuts are sometimes twice that of the carcass price (before VAT and margin), while the low-value cuts range from less than the carcass price to more or less in line with it.”

Regarding a new meat grading system, he points out that such a system will only focus on the prime cuts of a carcass and will have no impact on the low-value cuts.

Quality of meat

According to Prof Hugo, the marked increase in carcass weights these past few decades since the previous official block test has had a significant impact on the way carcasses ought to be managed. If managed incorrectly, the effect on meat quality could be detrimental.

Most large abattoirs, he explains, were built in the 1980s and 90s, and the infrastructure for chilling carcasses, among other things, was based on the prevailing carcass size at the time (around 210 to 240kg). Cold rooms are designed to accommodate and effectively chill a given number of carcasses of that weight. To grasp the challenges industry faces, he says, one must first understand the effects of chilling and electrical stimulation.

“If a carcass cools too quickly, before rigor mortis is complete, a phenomenon called ‘cold shrinkage’ presents and leads to tough meat. Electrical stimulation is applied to the carcass to accelerate rigor mortis. This prevents cold shrinkage. However, electrical stimulation also accelerates the release of tenderness enzymes.

“On the other hand, if the carcass cools too slowly, which is often the case in large carcasses, the muscles cool too slowly while the pH is still high.”

Carcasses currently weigh an average of around 280 to 300kg. If an abattoir were to hang the same number of sides in the cold room as in the past, the carcasses may cool too slowly because of the increased weight of warm meat. Applying electrical stimulation will lead to a rapid drop in the pH while the temperature of the meat is still high.

This is especially a problem if the pH drops below six while the meat’s temperature is still above 35°C. The protein in the meat starts to denature. One of these proteins is actomyosin which, if denatured, increases drip loss; another protein, myoglobin, affects the colour of the meat. The combination of low pH and high temperature can also damage the tenderness enzymes, leading to substandard ageing and therefore tougher meat.

These problems can occur even without electrical stimulation amid a quick drop in the pH and high meat temperature. Halting electrical stimulation to prevent the pH from dropping too quickly does not always help. There is still a risk, even if the carcass cools slowly. It is therefore necessary to adapt the cold rooms at abattoirs to accommodate larger, heavier carcasses.

It is important to perform regular standard block tests, says Prof Hugo. However, retailers conduct different block tests which results in considerable variation. The industry can benefit from a standardised block test performed by an independent institution. – Prof Arno Hugo, Department of Animal Science, University of the Free State, and Dr Frikkie Maré, CEO, RPO

For more information, send an email to Prof Arno Hugo at hugoa@ufs.ac.za, or Dr Frikkie Maré at frikkie@rpo.co.za.