Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

- With lobbies for and against the production and consumption of red meat and research on the impact of its production on the environment and the effects of consumption on human health, ear-catching statements are often loudly proclaimed.

- “For an individual, the risk of developing colorectal cancer because of their consumption of processed meat remains small, but this risk increases with the amount of meat consumed,” says Dr Kurt Straif, head of the IARC Monographs Programme.

- Cancer Research UK responded by pointing out that IARC is not saying that eating red and processed meat as part of a balanced diet causes cancer.

- Prof Hettie Schönfeldt of the Institute of Food, Nutrition and Well-being at the University of Pretoria highlights the fact that the IARC findings represent the opinion of a selected group of scientists, and not consensus within the scientific community.

- According to Prof Hoffman, producers must realise that the modern consumer is aware of the nutritional value of the food they choose to eat.

With lobbies for and against the production and consumption of red meat and research on the impact of its production on the environment and the effects of consumption on human health, ear-catching statements are often loudly proclaimed.

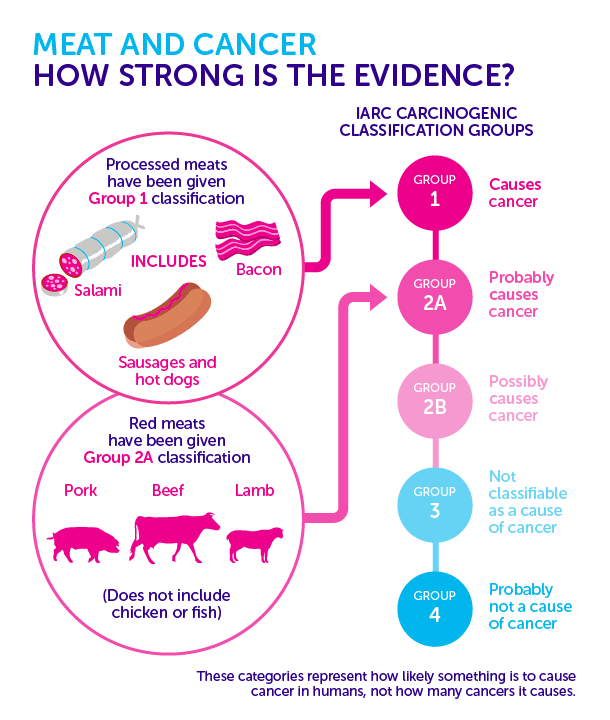

This was once again the case when the world recently took note of headlines stating that the results of a recent World Health Organisation (WHO) study link red meat to cancer. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the cancer agency of the WHO, evaluated the carcinogenicity of red meat and processed meat and proclaimed certain observations.

The following statement was released: “After thoroughly reviewing the accumulated scientific literature, a working group of 22 experts from ten countries convened by the IARC Monographs Programme classified the consumption of red meat as probably carcinogenic to humans (Group 2A), based on limited evidence that the consumption of red meat causes cancer in humans and strong mechanistic evidence supporting a carcinogenic effect.

“This association was observed mainly for colorectal cancer, but associations were also seen for pancreatic and prostate cancers. Processed meat was classified as carcinogenic to humans (Group 1), based on sufficient evidence in humans that the consumption of processed meat causes colorectal cancer.” While anti-meat lobbies welcomed the statement, red meat producers and value chain role-players followed with immediate responses questioning the statement and the legitimacy of the research.

“For an individual, the risk of developing colorectal cancer because of their consumption of processed meat remains small, but this risk increases with the amount of meat consumed,” says Dr Kurt Straif, head of the IARC Monographs Programme. “In view of the large number of people who consume processed meat, the global impact on cancer incidence is of public health importance.”

After the announcement was made, Cancer Research UK, a cancer research and awareness charity in the United Kingdom, responded by pointing out that IARC is not saying that eating red and processed meat as part of a balanced diet causes cancer. It is also not implying that meat is as dangerous as smoking, but merely points out that there is an associated risk.

Mainstream media

Various mainstream media articles followed the reports and in the process a number of facts may have been misrepresented. Firstly, the media focussed on the fact that processed red meat is classified as a Group 1 carcinogen, which places it in the same group as cigarettes, asbestos and other well-known carcinogens.

This, however, does not mean that eating red meat is as carcinogenic as smoking. “Not all Group 1 carcinogens carry the same risk. The classification simply means that the substance has been shown to be carcinogenic,” says Chelsea Harvey, an American journalist specialising in science, health and environmental reporting.

Another misunderstood detail is the level of risk associated with processed red meat. According to the report, eating 50g of processed meat daily increases the risk of colorectal cancer by 18%. “However, the statistic doesn’t mean that eating 50g of processed meat daily causes you to have an 18% total chance of developing cancer. It means you’re 18% more likely to develop cancer relative to whatever your initial, absolute risk already was.

For example, if you had a 10% risk of developing colon cancer to begin with, and you ate 50g of processed meat every day, your risk would increase by 18% of 10%. So your total risk would increase to 11,8%,” her article explains.

Criticism

Putting the report’s statements into context, Prof Hettie Schönfeldt of the Institute of Food, Nutrition and Well-being at the University of Pretoria highlights the fact that the IARC findings represent the opinion of a selected group of scientists, and not consensus within the scientific community. She further explains that this evaluation is based on existing scientific literature, not new evidence.

“Moreover, IARC conducts hazard analysis, not risk assessments. This distinction is important. It means that they consider whether meat at some level, under some circumstance, could be a hazard,” she explains. The agency itself explains this as follows: “IARC isn’t in the business of telling us how potent something is in causing cancer, only whether it does so or not.”

According to Louw Hoffman from the Department of Animal Sciences of the Faculty of AgriSciences at Stellenbosch University, some factors cast doubt on the credibility of the study. Critics are claiming that the group did not consider the complete body of literature in their study of previous research. “I personally think conclusions reporting associations such as this, contain certain weaknesses.

“If we say, for example, that cancer is associated with bacon, we have to remember that bacon is in most cases not eaten alone,” he explains. People would typically have bacon, eggs and toast. The association could therefore possibly be with eggs, toast or other factors included in their diet or lifestyle. “People typically eat a varied diet, but this type of analysis focusses only on one aspect of diet or lifestyle. Other food types, cooking methods or interaction between different foods are not considered.”

Prof Schönfeldt further says that there is no evidence that removing meat from your diet protects you from cancer. “In fact, a major long-term study by the University of Oxford has shown no difference in colorectal cancer rates between meat eaters and vegetarians.

Producer responsibility

According to Prof Hoffman, producers must realise that the modern consumer is aware of the nutritional value of the food they choose to eat. They are also increasingly aware of food production practices. Producers should therefore be aware that consumers take notice of such a study and that it may inhibit consumer confidence.

Producers should therefore do everything in their power to build consumer confidence and keep the nutrition and health of their consumer in mind throughout production. “A farmer should always ask himself: Would I eat this?” says Prof Hoffman. Producers and role-players in the red meat value chain have a responsibility to play a significant role in consumer education.

A local perspective

With South Africa in particular, various factors regarding meat consumption should be considered. Prof Schönfeldt points out that none of the 22 scientists from the ten countries that participated in the study, represents developing countries. “This is a shortcoming in relation to South Africa as a developing country with an emerging economy.” “Animal protein, such as red meat, is a favourite food in our diets, but the portions at population level still remain smaller than that recommended by the South African Food-Based Dietary Guidelines,” she says. On average, South Africans eat notably less protein source foods (11 to 18%) compared to levels recommended by the WHO, stating that 20% of total dietary energy should be from protein.

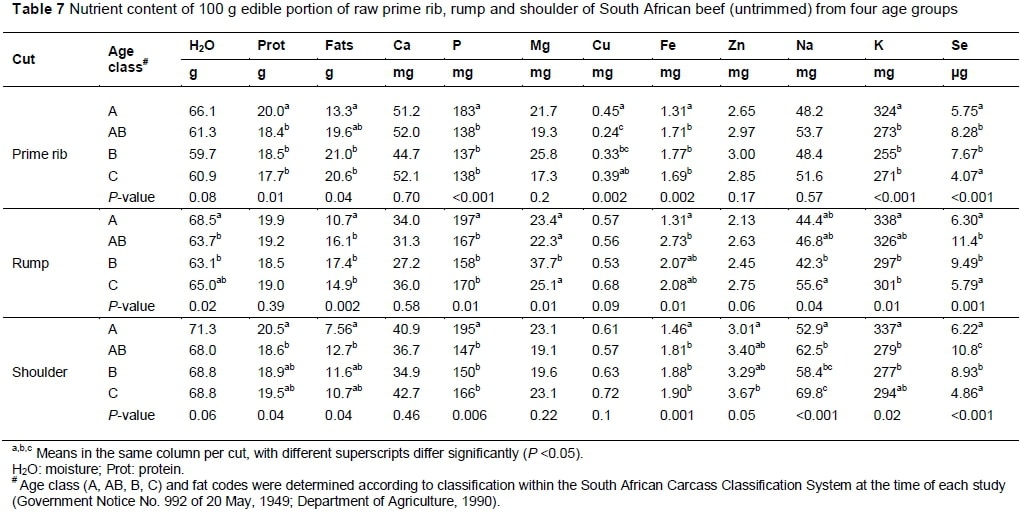

Local red meat contains less fat than that in most developed nations, and the composition of red meat indicates a reduction in total fat content over time. “The little fat that South African red meat does contain, has an excellent fatty acid profile,” adds Prof Hoffman.

Moderation is key

It is important to note that the IARC review does not advise people to stop eating processed meats, but indicates that reducing consumption of these products can reduce the risk of colorectal cancer. Prof Schönfeldt notes that cancer is a multi-complex problem that cannot be blamed on one specific food group. Prof Hoffman adds that moderation should be key with regard to what and how much you eat.

“Personally, I believe that red meat should be the anchor of any meal as it is protein dense. However, moderation remains key,” he adds. “Red meat plays an important role in a balanced diet, as it contains high biological value protein and important micronutrients,” Prof Schönfeldt concludes. – Marike Brits, FarmBiz