Kikuyu grazing into which ryegrass is sown in autumn, is the most common grazing system in the milk producing areas of the Southern Cape. Kikuyu is dormant during the winter months (June to September) and ryegrass is therefore sown to bridge the fodder flow gap created by this resting period – Italian and perennial ryegrass cultivars are commonly used.

Carrying capacity in winter

Due to the cold winters, shorter days and low light intensity in the Southern Cape in winter, the growth rate of ryegrass decreases to 20 to 30kg dry matter (DM) per hectare per day. This is significantly lower than the 60 to 80kg DM per hectare per day produced in spring and summer.

Only two cows per hectare can therefore be accommodated in winter. However, the average stocking rate on most farms that cultivate grazing under irrigation, is four to five cows per hectare. For that reason, surplus grazing in spring and summer are ensiled and used during winter to bridge the roughage shortage gap.

Read more about buying dairy cows.

Below average rainfall was recorded for the spring of 2019, which meant that considerably less silage was produced on many farms. Roughage shortages can therefore be expected in the winter of 2020.

Lucerne hay and silage

Two strategies are generally used to overcome roughage shortages. One is to buy in roughage such as lucerne hay and the other is to feed some form of silage.

Lucerne is expensive. It usually has to be transported over long distances and transport costs are therefore a contributing factor. In addition, smaller farms do not necessarily have the storage capacity to store bulk quantities of lucerne.

Silage, on the other hand, should preferably be available on the farm and many farmers plant maize to produce silage. However, maize silage yields were also affected by the drought.

Find out more about how silage is made.

If one decides to purchase silage, it is important to determine its moisture content and price per ton DM. As silage is a perishable product, feed-out needs to occur within one to two days once it has been exposed to air. This is why it is neither practical nor cost-effective to transport silage over long distances.

Ring feeders are generally used for both lucerne and silage, with a resulting 10 to 20% that can easily be wasted.

Starch vs high-fibre concentrates

In winter cows are typically kept on grazing during the day and then moved to an overnight camp, where they have access to lucerne or silage, after the mid-day milking. They also receive extra concentrates in the milking parlour.

These concentrates are usually high in energy due to the high levels of maize in the mixture. This also increases associated costs. When the concentrate levels in the ration is increased, profit per litre of milk then decreases due to the higher feed costs.

This leads to an important question: Is it possible to replace such a highly digestible, high-starch concentrate with a low-starch, high-fibre concentrate that is still digestible, without adversely affecting milk production or rumen health? The high concentration of neutral detergent fibre (NDF) can play a part in keeping the rumen’s pH balance stable, as well as leaving microbial activity unaffected.

An alternative to lucerne?

But by how much can such a high-fibre concentrate ‘stretch’ the available grazing? If cows are fed higher levels of concentrate in the milking parlour and if they can cope with less grazing, it might be an alternative to purchasing lucerne. It is also very convenient to feed concentrates in the milking parlour; no additional labour or infrastructure is needed and wastage is minimal.

However, lucerne prices are currently high, ranging between R3 500 and R4 000/ton. A 15% wastage during feeding increases the cost to around R4 100 to R4 700/ton.

How will a high-fibre concentrate fed at higher levels affect milk production? Will it be able to address the problem of grazing shortages without compromising the rumen health of cows?

New research

In a bid to find answers to these questions, Lobke Steyn, an MSc student at Stellenbosch University, conducted a study at the Outeniqua Research Farm near George under the guidance of Prof Robin Meeske.

In the study 48 cows were divided into three groups of 16 each and left to graze separately for a 92-day period in winter. High-fibre concentrates were fed at 4, 7 or 10kg per cow per day. The concentrate contained 13% maize, 30% hominy chop, 39,1% bran, 10% Gluten 20, 4% molasses, 2,2% feed lime, 0,6% salt and 0,5% premix.

The energy content of the concentrate was 10,6MJ ME/kg DM, crude protein 14,5% and NDF 23,1% on a DM basis. The grazing allocated for cows on the low, medium and high concentrate treatment was 10, 7 and 5kg DM, respectively.

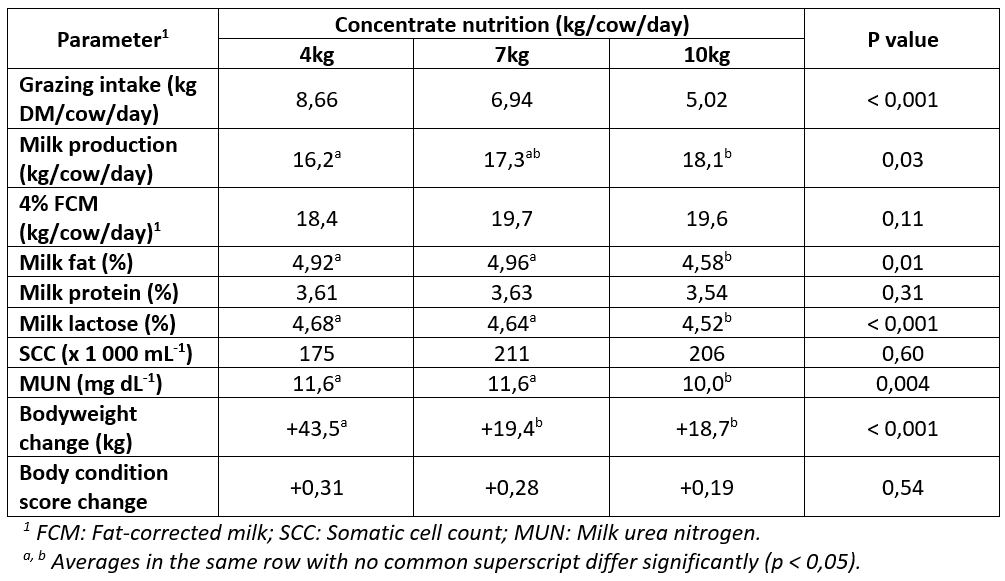

The groups of cows grazed day and night on separate grazing systems. Milk production was measured during each milking and samples were taken every second week for analysis. The cows’ weight and body condition score were also determined at the beginning and end of the study. Grazing yield was measured continuously with a rising plate meter before and after grazing. The results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Grazing intake, milk production, milk composition, bodyweight and condition of cows that received 4, 7 or 10kg high-fibre concentrate (16 cows per treatment).

Results of the study

Grazing intake decreased significantly as the levels of concentrate fed increased. This led to a stocking rate of 2,3, 2,9 and 4 cows per hectare for the low, medium and high concentrate treatment. By feeding high levels of a high-fibre concentrate, the roughage requirement was reduced by 40%.

There was no difference in the milk butterfat percentage in the cows in the low and medium concentrate groups; however, it was lower in the high concentrate group. This indicates that fibre digestion was slightly impaired in the high concentrate group. This was to be expected as feeding a high-level concentrate, and even a high-fibre concentrate, leads to a drop in the rumen pH, which reduces the activity of the bacteria that digest cellulose.

Furthermore, the acetic acid concentration decreased, which resulted in a decrease in the butterfat percentage. However, milk protein did not respond readily to ration manipulation, and no difference was noted between the three treatment groups. Somatic cell counts also remained constant and udder health was maintained throughout.

Bodyweight gain was higher on the low concentrate treatment, which can be attributed to the higher grazing allocation. No change was noted in the body condition scores; in fact, a slight increase in body condition was noted in all three groups. This is, however, expected in cows in mid- to late-lactation. Rumen health was also maintained in all three groups, even in the high-level concentrate group.

Good news for livestock farmers

This study has shown that it is indeed possible to ‘save’ your available grazing by partially replacing it with higher amounts of high-fibre concentrate. This approach can therefore be used successfully and is a practical alternative to purchasing lucerne during times of roughage shortages in winter.

Read more about the use of calcium binders in the steam-up phase.

Prof Robin Meeske is a specialist scientist at the Western Cape Department of Agriculture. He works at the Outeniqua Research Farm near George. For more information, phone him on 082 908 4110 or send an email to robinm@elsenburg.com. – Prof Robin Meeske and Izak Hofmeyr, Stockfarm