Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

There is ample scientific evidence indicating that the variability of climate over the past two decades has dramatically altered the production environment and foundation of livestock farming in Southern Africa. In the long run, this will have a potentially disruptive effect on livestock production and food security.

Are you a climate-smart ambassador?

Estimates indicate an increase of 1°C per year in the average temperatures across Southern Africa (compared to 0,65°C worldwide), as well as more erratic and extreme rainfall, with wet periods becoming wetter, dry periods becoming drier, and an unprecedented increase in the CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere.

For livestock farmers, this means having to farm livestock that can endure increased heat stress, greater runoff and rainwater losses, accelerated soil erosion, as well as longer and more intense droughts, although not an increase in the number of droughts.

Climate-smart agriculture = the future

Livestock farmers who can adapt to the challenges of this volatile situation will be richly rewarded. Those who do not make the necessary climate-smart adjustments are likely to disappear from the forefront and make but a small contribution to future production. Livestock farmers need to find ways to become more sustainable and resilient, despite the increasingly volatile climate.

Many analysts believe that so-called climate-smart agriculture is the answer. By definition, climate-smart producers apply principles and practices that increase biodiversity, restore soil health, improve the water cycle and restore ecosystems to their full production potential, resulting in increased yields per hectare, better and more stable yields, and less sensitivity to volatile climate patterns.

The expected increased volatility in rainfall, coupled with extended and more intense droughts, embody the proverbial elephant in the room when it comes to climate-smart livestock farming. It is also the efficient use of rainwater that will ultimately be a deciding factor, rather than the amount of rain that falls.

Precipitation in the water cycle

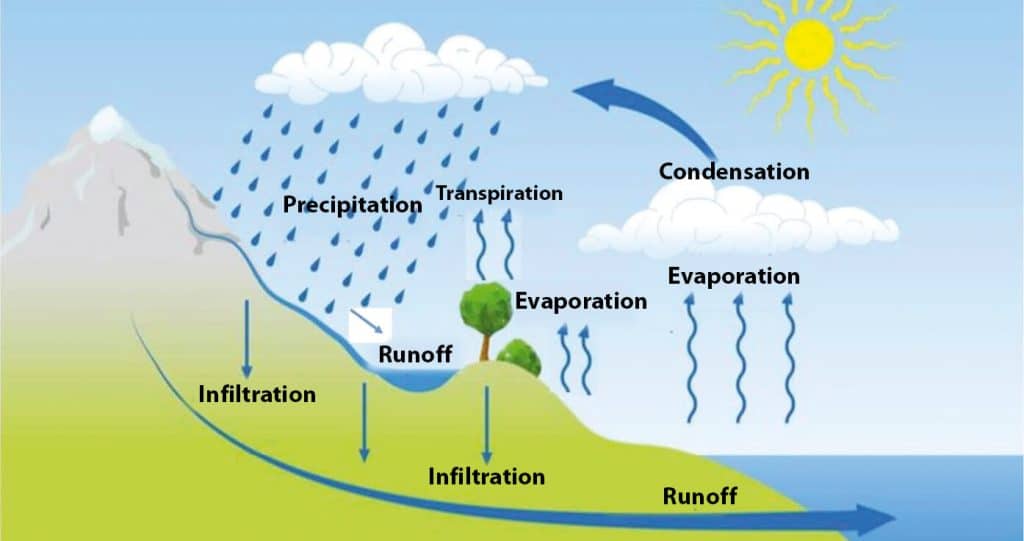

To better understand the concept of rainfall efficiency, a basic understanding of the water cycle is needed (Figure 1). Let’s start with the precipitation portion of the water cycle.

Precipitation occurs when the water vapour in the air condensates into the form of clouds, and gravity then draws it back down to the earth in some or other form. The forms in which precipitation occurs are rain, drizzle, sleet, snow and hail.

Precipitation has one of two outcomes: it can evaporate before it hits the ground, or it can reach Mother Earth. Up to this point, the producer has no control over what happens to it. He or she does, however, play a big role in what happens with the water that does in fact fall on his or her soil.

The precipitation that falls on the ground can either seep into the soil or run off, ending up in rivers and streams. Water that runs off is a loss for the livestock farmer, as it does not contribute to the veld’s production, even if it measured well in the rain gauge.

Influencing factors up until infiltration

The amount of water that seeps into the soil is determined by several factors. First, the denser the plant cover, the slower the flow of water over the soil and the more time the water has to seep into the soil. The density of the plant cover is determined by the condition of the veld, the occurrence or absence of bare areas, and the occurrence or absence of erosion ditches and dongas.

The density of the plant cover can be maximised by applying good grazing management. Bare patches can be repaired by applying hoof action, by mechanically loosening the topsoil using implements such as a chisel (ripper), scallop or butting plough, or by covering the bare patches with organic material such as garden waste and rotting hay bales.

The purpose of all these actions is to reduce the speed at which the water flows across the veld and bare patches, as well as to catch water so that it seeps into the soil over time. Erosion ditches and smaller dongas can be stabilised by packing stones and old tyres, while stone baskets (so-called gabions or barricades) can be used in smaller dongas.

Over time, the erosion ditches will fill up with sludge to the extent where it becomes completely covered in plants, which in turn improves the infiltration of runoff water instead of allowing further runoff.

Secondly, the greater the variety of plant species that cover the soil (biodiversity), the greater the occurrence of micro-organisms and organic matter content within the soil, and the better the infiltration of the rainwater. It also increases the soil’s ability to store water in the soil profile before it becomes saturated.

The better the condition of the veld, the more plant species it will carry. Producers can directly influence the condition of the veld on their farms, and thus also the biodiversity above and below the soil, by applying good grazing practices.

Drainage and evaporation

The water that seeps into the soil can either drain very deep and replenish the groundwater (deep drainage), or it can evaporate directly from the bare soil surface. It can also be absorbed by the vegetation and then, through transpiration, return to the atmosphere.

Deep drainage is not considered a loss of water, as it replenishes the groundwater. This is actually a huge asset. The more water penetrates the soil profile, the better the chances of deep drainage and the fewer the problems with dried up boreholes.

The water that is absorbed and transpired by the plants is essential for the process of photosynthesis. The more water transpires, the more feed is produced. The water that goes back to the atmosphere through the vegetation is the only part of the precipitation that contributes to plant production – it is the efficient portion of the rain.

The water that evaporates directly from the soil surface is lost to the livestock farmer, as it is not absorbed by plants and therefore does not contribute to veld production.

The role of veld condition

We naturally want the water that transpires to be converted into feed as efficiently as possible. When unwanted invasive shrubs absorb and transpire the water, they produce tons of plant material but very little fodder. Similarly, there are grasses that, for example, produce significantly less feed than other grasses, even though they consume the same amount of water.

Annual grasses use their water mainly to produce seed instead of feed, because seed is their mechanism of survival. In contrast, good grazing grasses utilise a much larger share of their water consumption for the production of feed. They are therefore better at efficient water consumption. The better the condition of the veld, the greater the portion of these productive plants that represent the species composition.

Producers have control over the species composition of their veld, firstly by controlling unwanted invasive or alien plants, and secondly by ensuring that the veld is in excellent condition, as those plants with the best water consumption efficiency are found in good veld. This demands careful grazing management.

Producers also have control over the animals that have access to the feed that has been produced. What good is a farm that produces excellent feed, only to have it consumed by poor quality livestock or wasted through poor herd management practices? Climate-smart livestock farmers will always strive to realise maximum profit from every kilogram of feed produced.

Let every drop work for you

The water that evaporates from the bare soil surface or open waters (the sea, lakes and dams), plus the water that transpires through the plants, all collect in the atmosphere and condensate to form clouds and cause precipitation, which completes and repeats the water cycle.

This model provides a very basic explanation of the water cycle, but what it clearly illustrates is that only that part of the rainfall that seeps into the soil and is transpired by the good and desired grazing plants, will contribute to efficient feed production and therefore efficient rainfall.

This is the only part of the water cycle that leads to feed production. The rest is lost to runoff, deep drainage or evaporation from the soil surface.

The rain in the rain gauge is therefore not all that counts – it is the water that eventually ends up in the soil and that is used by good plants to produce feed, that makes all the difference. It embodies efficient rainfall and should be the focus of climate-smart livestock farmers. They make every drop of water work for them!

In the next four articles in this series, we will be looking at climate-smart veld management, radical veld improvement, climate-smart herd management and climate-smart drought management in more detail. – Dr Louis du Pisani, independent agricultural consultant

For more information and references, contact Dr Louis du Pisani on 082 773 9778 or Ldupisani@gmail.com.