Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

Most commercial farmers know that mating cattle of different breeds results in increased performance in the crossbred calves relative to the average of the parental breeds. This article explains the benefits and economic importance of crossbreeding.

There are two primary advantages to crossbreeding:

- Breed complementarity: the ability to combine traits from two or more breeds into one animal. For example, some breeds are known for adaptability or reproductive performance, whereas other breeds would add additional growth performance to the progeny.

- Hybrid vigour, also known as heterosis: the tendency of crossbred individuals to show qualities superior to the average of their parents.

Heterosis is not the same for all traits, and generates the largest improvement in lowly heritable traits, such as reproduction and longevity (Table 1). The greatest impacts on profitability from heterosis are the increases in overall production and longevity of crossbred cows.

Table1: Heritability and heterosis for important traits.

| Trait | Heritability | Level of Hesterosis |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal ability Conception Reproduction Health Calf survival Cow longevity Overall cow productivity | Low | High (10 to 30%) |

| Growth rate Birthweight Weaning weight Yearling weight Milk production | Medium | Medium (5 to 10%) |

| Mature weight Skeletal measurements Carcass / End weight | High | Low (0 to 5%) |

Measuring heterosis

Heterosis can be measured. For example, Breed A averages 200kg at weaning, and Breed B averages 240kg at weaning. When crossed, the A × B calves weigh on average 230kg at weaning, which is higher than the mid-parent average of 220kg. The hybrid vigour from this mating can be calculated with the following equation:

Hybrid vigour = (Crossbred performance average − Straightbred performance average) ÷ Straightbred performance average = (230 − 220) ÷ 220 = 4.5% improvement

Individual heterosis

The hybrid vigour for the F1 or first-generation cross in this example is 4.5% above the average of the parent breeds for weaning weights. This is known as individual heterosis and is generally seen in growth traits of the crossbred offspring.

Maternal heterosis

Maternal heterosis is the increase in average production observed in crossbred F1 cows compared to straight-bred cows. They often have increased calving percentages, wean heavier calves and have greater longevity. Enhanced production from the crossbred cow is the primary benefit of a planned crossbreeding system.

Crossbreeding systems

There are different ways of benefitting from crossbreeding in which one can utilize both individual and /or maternal heterosis.

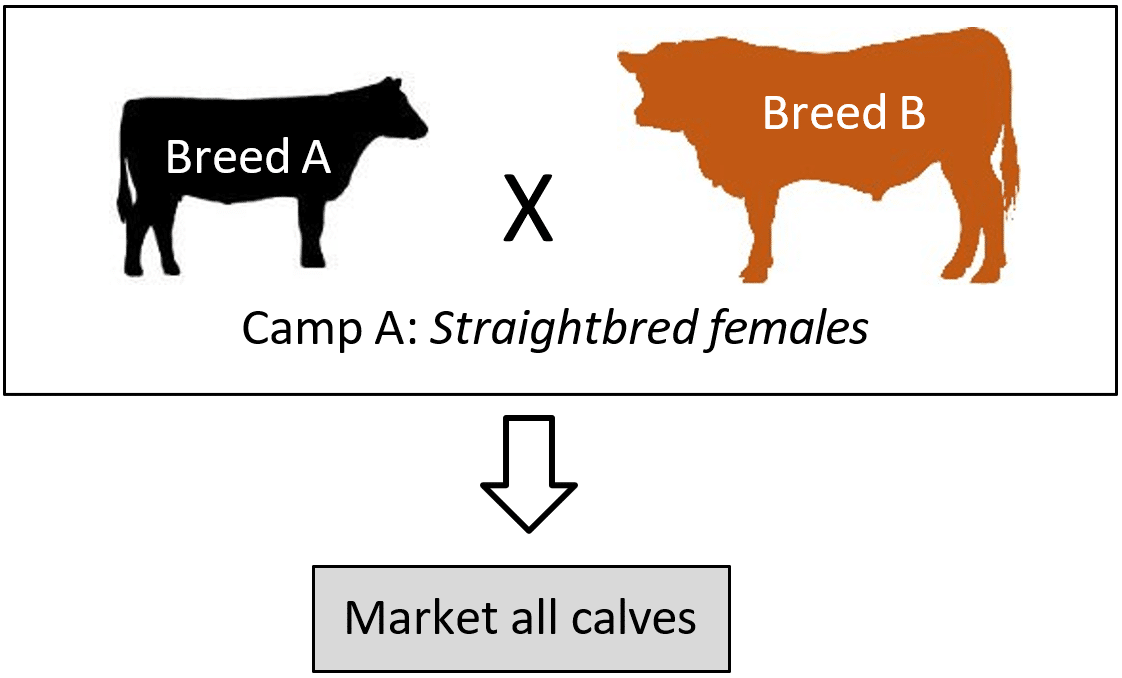

Two-breed terminal crossbreeding system

- Simple, basic crossbreeding system

- Breed A x Breed B

- 100% individual heterosis and no maternal heterosis

- All F1 progeny are marketed

- F1 replacement heifers can be sold as breeding females

- Replacement heifers are purchased, or homebred.

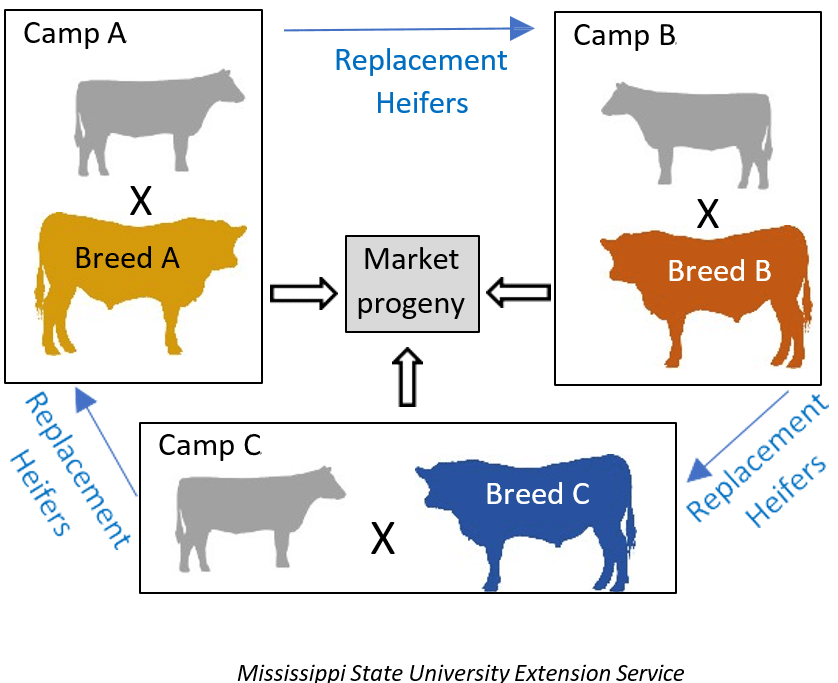

Three-breed terminal crossbreeding system

- The most hybrid vigour of any crossbreeding scheme

- Crossbred AB cows X Breed C sires

- 100% individual and 100% maternal heterosis

- All F1 progeny are marketed

- Purchased F1 replacement heifers should be environmentally adapted with the necessary maternal capacities.

- Terminal sires can be selected only on growth and carcass with no attention to maternal traits.

Sustainability

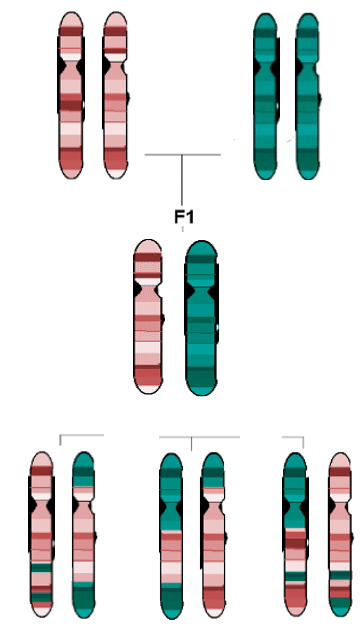

Hybrid vigour yields its greatest advantages in first-generation crosses (F1) because hybrid vigour is not transmitted from generation to generation without continued crossbreeding. When crossing F1 with F1, the favourable combinations deteriorate due to recombination, and in practice, the genetic make-up of the F2 progeny are somewhere in between the parent breeds. The heterosis effect is lost.

In terms of hybrid vigour, the ultimate female is therefore the first-generation cow (F1) from the mating of two purebreds from different breeds. The challenge, however, is to maintain a continuous supply of F1 crossbred heifers as a purebred parent population would need to be maintained or replacements would need to be purchased elsewhere, which most producers are reluctant to do. This problem is overcome by various crossbreeding systems which have some degree of heterosis but can become very complicated. Composite breeds also utilize heterosis without the need for continuous crossbreeding.

Two-breed rotational crossbreeding system

- Effective and relatively simple

- Females sired by Breed A are mated to sires of Breed B, and females sired by Breed B are mated to sires of Breed A.

- Heterosis stabilizes at 67% of potential individual and maternal heterosis after 6 generations.

- As replacement heifers sired by Breeds A and B are retained, both breeds should therefore have maternal characteristics.

- Two sires are required, therefore at least 50 cows and two camps are needed.

Three- and four-breed rotational crossbreeding systems

- Similar to the two-breed rotation with another breed added.

- Three-breed system: Breed A sires are mated to females sired by Breed B, Breed B sires are mated to females sired by Breed C, and Breed C sires are mated to females sired by Breed A.

- Hybrid vigour stabilizes after several generations at 86% (3 breeds) and 93% (4 breeds) of potential individual and maternal hybrid vigour.

- Replacements are retained from within the herd.

- Three sire-breeds require at least 75 cows in 3 camps, while four sire breeds require at least 100 cows in 4 camps.

- The ability to locate 3 or 4 breeds that fit a given breeding scheme can be challenging.

- For only a slight gain between 3- and 4-breed systems, the system becomes very complicated. Benefits may not outweigh the cost.

Three-breed roto-terminal crossbreeding system

- Extension of the two-breed rotational system with a terminal sire added.

- Some cows (especially heifers) are placed in the two-breed rotation to produce replacement heifers, and the rest (older cows) is mated to a terminal sire to produce calves that are all marketed.

- The breeds used in the two-breed rotation must still be selected for the criteria specified in the rotational programs.

- Terminal sires can be selected for increased growth and carcass traits to maximise production from the cowherd.

- More labour, management, and breeding pastures are needed than in a two-breed rotation.

Sire rotation crossbreeding system

- Common crossbreeding system.

- One breed of sire is used for 4 to 6 years, and then the sire breed is changed.

- This system can use two, three or more breeds.

- As only one breed of sire at a time is required, one camp and any herd size are sufficient.

- A relatively high level of heterosis is maintained, usually >50% depending on the number and sequence of sires used.

Composite breed

A composite breed has traits of economic importance from many breeds which is then maintained as a straight-bred herd. This system has the advantage of being very easily managed once the composite breed is established (which takes many generations/years) and it can capture a higher amount of existing genetic variation among breeds than other crossbreeding systems.

Table 2 provides a summary of beef cattle crossbreeding system details and considerations.

Table 2. Summary of crossbreeding systems by amount of advantage (% increase in calf weaned per cow exposed) and other logistical considerations (From Crossbreeding for the Commercial Producer, www.eBEEF.org, 2017-2)

| Type of system | Scheme | Advantage (%)a | Retained heterosis (%)b | Minimum # of camps | Min. herd size | # of breeds |

| 2-breed terminal cross | T x (A) | 8.5 | 0c | 1 | Any | 2 |

| 3-breed terminal cross | T x (A*B) | 24 | 100 | 1 | Any | 3 |

| 2-breed rotation | A*B rotation | 16 | 67 | 2 | 50 | 2 |

| 3-breed rotation | A*B*C rotation | 20 | 86 | 3 | 75 | 3 |

| 2-breed rotational with terminal sire | Overall | 21 | 90 | 3 | 100 | 3 |

| Composite breeds | 2-breed 3-breed 4-breed | 12 15 17 | 50d 67 7 5 | 1 1 1 | Any Any Any | 2 3 4 |

| Rotating unrelated F1 bulls | A*B x A*B A*B x A*C A*B x C*D | 12 16 19 | 50 67 83 | 1 1 1 | Any Any Any | 2 3 4 |

b Relative to F1 with 100% heterosis.

c Straight-bred cows are used which have 0% maternal heterosis; calves exhibit heterosis which is responsible for the expected improvement in weaning weight per cow exposed.

d Estimates of the range of retained heterosis.

Conclusion

Crossbreeding systems range in complexity from very simple programs such as the use of composite breeds, which are as easy as straight breeding, to elaborate rotational crossbreeding systems with four or more breeds. A crossbreeding system should take advantage of breed complementarity and heterosis. Although the individual change in some traits is small, it has been found that lifetime production can increase by more than 20% in programmes designed to capture both individual heterosis in crossbred calves and maternal heterosis in crossbred cows. It is also important to select all bulls on breeding values for the desired traits – starting out correctly will also increase gains. – Dr Helena Theron, SA Stud Book

References and more information available from the author at email helena@studbook.co.za